KC COLUMN: THINGS THAT ARE GONE

by KC Carlson

Wow, it’s been a weird week (or so) for the world of comics as three long-running icons of the industry virtually vanished overnight. None of their disappearances were all that surprising — but all three can be said to mark a proverbial End of an Era.

Things That Are Gone #1: The Comics Code

As you’ve probably seen elsewhere around the ‘net, both DC Comics and Archie Comics announced that they will no longer be using the Comics Code. While this sounds like big news, once the details came out, it was actually pretty tiny news. DC was only using the Code for a handful of books (mostly their kids’ titles), and it turns out that Archie stopped using the Code about a year ago, but nobody knew it because the Code symbol continued to appear on their books. There is a bigger story here, one that, so far, is technically unsubstantiated (and may never officially be, because of the circumstances). That real story is that the Comics Code Authority is probably dead. Talk about burying the lead.

[For a great wrap-up of recent Code-related events, as well as a look at some of the history of the Code, please check out this article at ComicsWorthReading.com, written by Johanna Draper Carlson (who, in her not-so-secret identity, is also my wife). Be sure to check out the links for even more info, especially the one for Westfield’s own Bob Greenberger, where he discusses his personal dealings with the code as the longtime DC editorial administrator. Also look at Christopher Butcher’s well-founded speculations for what may really be going on.]

The Comics Code is dead because the Code was entirely funded by the companies that used it, and now that no comics publishers are using it any more… well… no money, no Code. Because the Code Authority was largely the sum of its parts (and generally worked anonymously behind the scenes), chances are there will not be any sort of formal or official announcement of its actual death. It’s just gone.

A Little History, Please…

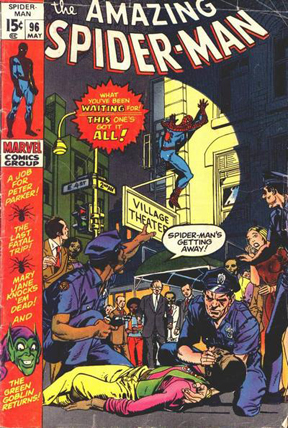

The Comics Code had been on life support for a long time. Current history has it that the Code became irrelevant when Marvel dropped it entirely in 2001, but as comic historians like Mark Evanier have pointed out, the Code functionally became a non-entity back in the early 70s. Comics’ biggest story without the Code — Stan Lee’s infamous “drug” issues of Amazing Spider-Man (#96-98) in 1971 (the first mainstream comics printed without Code approval) — spurred big changes in the Comics Code, largely reflecting the changing times. Once the Code was changed, DC then went ahead with their drug story “Snowbirds Don’t Fly” in Green Lantern #85-86 (also 1971). It wasn’t widely known, but the Code continued to change over time, again reflecting changing standards, as publishers periodically wanted a loosening of the restrictions. Since they were largely footing the bill… quid pro quo.

The Code was first established in the 1950s, following the Seduction of the Innocent/Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency hearings and public outcry over the “dangers” of comic books for children. It was a rabidly promoted self-regulatory board set up by many of the more popular comic book companies, including National (DC), Timely/Atlas (Marvel), and Archie Comics. Notably, Dell, one of the largest companies selling comics for kids (including virtually all the Disney, Hanna-Barbera, and MGM cartoon characters), never joined the Code, and they never suffered for not displaying it.

The Code’s biggest supporters among comics publishers have been gone for a while now. John Goldwater (Archie Comics) passed away in 1999, and Paul Levitz (DC Comics) was no longer in a position of authority as of 2010. Levitz was seen by some of the industry as the last defender of the Code, mostly as a long-standing historical tradition. Some have speculated that Marvel’s move to drop the Code in the 1990s was largely aimed at deliberately embarrassing Levitz and DC, creating a PR stunt to make Marvel look young and hip and DC look like dinosaurs. In reality, DC had already cut back on using the Code years before, first with their Direct Sales-only titles (many of which contained mature themes, but which also bypassed traditional newsstands), and again later with the introduction of the Vertigo line, which were published with a “Mature Readers” label.

Curious About the Code

When I first started working at DC (technically in 1989, but I didn’t become a line editor until 1992), I was especially interested in finding out more about the inner workings of the Comics Code, since I knew a lot about its history (having done major papers about it for both high school and college), but very little about its administration and inner workings. I was in for a major disappointment in this area.

Generally, when new editors are hired or moved over to full editing, they inherit the files of the previous editor, especially with long-running projects. So, traditionally, one of the things that a new editor taking over existing projects has to do is sit down and read the files of the outgoing editor. However, one thing I expected to find in the files was missing — a copy of the Comics Code. I just assumed that every editor would have a permanent copy of the current guidelines.

After checking with Bob Greenberger (unofficial master of “where everything was” in both the DC Universe and the DC offices), I discovered that there were very few copies of the Comics Code in the DC offices. Part of that conversation went something like this:

Bob: What do you want the Code for?

Me: I just want to read it. Shouldn’t we all know what’s in it?

Bob: You know comics history, right? So you pretty much know what’s in there, right?

Me: Yes, but…

Bob: So, what’s to know? If you do something wrong, somebody will let you know.

While I was editing for DC, I had very little contact with the Comics Code. The Legion of Super-Heroes title hadn’t been Code-approved for years. (Probably since the old DC “hardcover/softcover” days. Bob Greenberger tells me that the Direct-Only versions of these books were not Code-approved, but when the “softcover” newsstand reprint versions were published a year later, they then went to the Code for approval — and there were occasional changes, especially in New Titans/Tales of the Teen Titans when it came to Starfire and her various states of undress.) Later, when Legionnaires and Valor debuted, they also were not Code-approved (except for the first few issues of Valor, for some reason that I do not remember). Not that it made much difference — I don’t think we got anywhere close to doing anything which might have run afoul of the Code in the LSH-related books. We were all interested in doing stories that could be read by all ages (before that phase became anathema to modern-day superhero fanboys).

Code Red (and Blue)

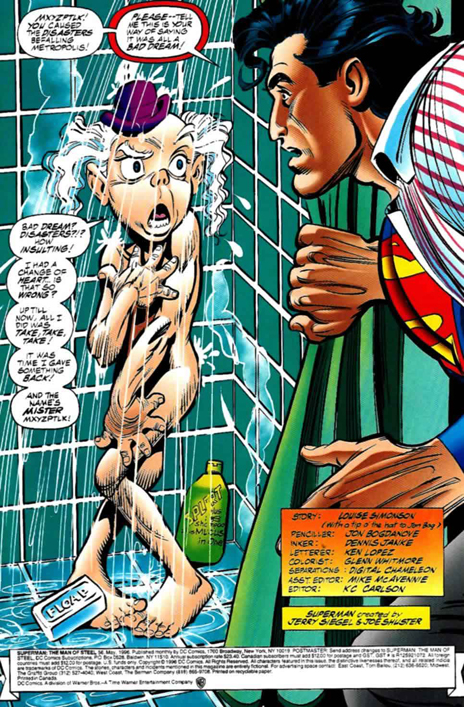

The one time I actually did run afoul of the Comics Code was for something that I never would have expected to be a Code-related problem. Throughout 1995-96, the crew producing the Superman line of comics were working on a long storyline where many of the ongoing Superman characters were faced with bizarre incidents (including the sudden reappearance of long-missing character Lori Lemaris). Many of the incidents were referred to as a “plague of bad luck”. At the climax of the story, it was time to reveal exactly who was behind all of the bizarre incidents.

In May of 1996 (cover date time), in Superman: Man of Steel #56, the villain behind it all was revealed as — Mr. Mxyzptlk! Because we were all feeling silly, Louise Simonson and Jon Bogdanove decided that the perfect place for the “reveal” was in Clark Kent’s shower. (Evoking the return of Bobby Ewing in Dallas.) Since Mxy was naked, and not wanting impressionable readers to see Mr. Mxyzptlk’s… uh… “mister”, Bog thoughtfully covered him up — with the Comics Code seal.

Funny gag, we thought. Unfortunately, the Comics Code people didn’t see it that way.

I first found out about the problem when Bob Greenberger suddenly appeared in my doorway (as he was wont to do), a few weeks after putting the finished book into production. “Oh, you’re not going to believe this one…” was Bob’s famous opening line. He then proceeded to explain to me that S: MoS #56 wasn’t going to get code approved unless changes were made.

“But if we lost the Code seal from the artwork, wouldn’t that actually make the drawing more obscene?” was my smart-ass reply.

“Why, yes, it would,” replied Bob, not missing a beat. “However, it also means that there wouldn’t be a Code seal on the cover of the book, and we (meaning DC) can’t have that happen on a Superman title.”

A few minutes of ultimately pointless arguing followed, including my question of what specific point of the Code we were violating. Answer: there wasn’t one — it turned out that the Code people were mostly upset that we were making fun of the Code and concerned that we were trying to somehow undermine it. I replied that we really weren’t and asked if I could speak with somebody at the Code about it, but I was told that wasn’t the way things were done. It soon became a forgone conclusion that I was going to have to lose the Code seal in order to get the Code approval (which still makes my head spin). Weezie and Bog were as incredulous as I was about the circumstances, and they fortunately (but reluctantly) said okay to the change. As you can see, the Code was hastily replaced by a CENSORED banner for publication. Oh well.

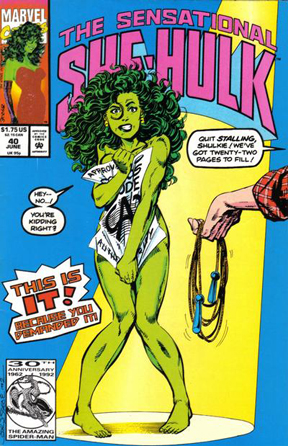

It wasn’t until much later that I remembered this cover:

Same gag (sorry John!). Published four years before the Superman story. Note the Comics Code Seal in the upper left corner, next to the issue number. Bottom line, by then not only was the Comics Code often inconsequential, it was also maddeningly inconsistent.

The Code: Psychological Deterrent?

I had one other kinda Comics Code-related thing happen while at DC, although the Code itself wasn’t a part of the story. Early in my editorial career at DC, a prominent indy-style creator approached me about developing The Creeper for an ongoing series. I was quite excited by this prospect, as said creator was already well-known for his atmospherically quirky projects.

I started paving the way for the potential series by having The Creeper “killed off” in the pages of Eclipso, a book I was currently editing. Said creator and I spoke on and off about the project for awhile (partially derailed while I was busy with Zero Hour), but the project ultimately unraveled. I discovered that the creator was uncomfortable — despite initial excitement about working within its limitations for the first time — working on a project that was going to be Comics Code-approved. Turned out that the more he thought about it, the concepts that he wanted to explore for both the character and the series were probably going to be a problem under the Code. Despite my encouragement, he couldn’t see it as a comfortable working atmosphere, especially coming from very personal projects with almost total freedom. Reluctantly, we both backed away from the Creeper revamp.

This all took place in the early 1990s, just as the Vertigo line was getting established and at a time where most all “mature” work was being pushed in that direction. DC mainstream was kept for more traditional superhero comic work. As The Creeper was perceived as a DC character, transitioning him to Vertigo would have been problematic (and probably not desirable from the DC point of view at the time). In just a few years, things would be wildly different. (Nevertheless, and bad timing aside, I’m withholding the name of this creator because it was, after all, a not-fully developed project, not one that exists on his resume. But, man, it would have been SO cool…)

Things That Are Gone #2: Wizard Magazine

A lot of folks seemed surprised about the quick shutdown of Wizard magazine, but my reaction can be summed up by the subject of the email I sent to my wife Johanna (who’s provided an excellent rundown of recent Wizard activities at ComicsWorthReading.com) on the day the news broke: The Other Shoe Dropped.

For the past couple of years, Wizard has been in the business of going out of business, at least in terms of their magazines and website, both of which have been in disarray since I can remember. I thought that the magazine was already gone, since many of the local comic shops I frequent had already stopped carrying it for the racks. Honestly, I had stopped even thinking about it until a new grocery store chain opened up in town, and — lo and behold — there was Wizard on their magazine rack. So yes, if I wanted to, I could get the new Wizard at the same time I was restocking Hot Pockets and SpaghettiOs! (Which has a higher fiber content and definitely more nutrients than Wizard. Also, SpaghettiOs led the way in building strong bodies, while Wizard just had an unhealthy fixation with body parts. And thanks to Jim Gaffigan, we now also know that Hot Pockets are way more funnier than Wizard ever was.)

Wizard promises to have an increased internet presence, although many have already pointed out that they are already light years behind other internet news outlets like Comic Book Resources or Newsarama. So they’ve got a lot of catching up to do.

The company also has their ever-growing lineup of conventions, which I recommend if that’s the only comics show in your area. If your idea of a good show is standing in line for hours to get an autograph and maybe ten seconds to speak with your favorite creator, or you just gotta have an 8”x10” (for an additional fee) from your favorite semi-employed actor or wrestler, or if you like asking yourself “Hey, shouldn’t there be some comics-related programming going on somewhere?” — then a Wizard World show is your show.

If you’ve read this far, you might think that I’m not too fond of Wizard. And you’d be right. In so many ways, Wizard derailed the medium’s progress into a major artform and has repeatedly dumbed down the level of comics discourse and discussion during its existence. The emphasis on event-style storytelling over character and emotionally driven work can largely be laid at Wizard’s feet, as well as overemphasis on media tie-ins, which often dwarfed coverage of the comics themselves. Wayne Markley’s recent Westfield column calling Wizard “the fanboy’s version of Playboy” is not far off the mark, and his comparison of the magazine’s fans with those of AVN (Adult Video News magazine) is spot on.

Further, as I see more and more (actually less and less, as I find myself dropping their books) comic work from former Wizard staffers (most notably J. T. Krul and editor Brian Cunningham), all I can say is they may have no idea how to tell a truly great comic book story, but they sure know how to swing a dead cat. I don’t want to blame them alone, since many people have had their hands in this current darkening of superhero comics, but I can’t help connecting the “shock for its own sake” storytelling that has appeared under their names with the exploitation Wizard magazine brought us.

So, no, I won’t miss Wizard. But I am sad that they’re gone, as it’s another sad reminder that the once-flourishing world of fanzines and prozines (at least in their printed formats) is close to total extinction. In America, all that’s really left is the venerable Comics Buyer’s Guide.

Things That Are Gone #3: The Human Torch

Sorry for the spoiler, although I’m guessing the major media (as well as Marvel itself) beat me to that little secret. But that’s not what this is about. This particular ending is making me think more about the future.

Bottom line, Fantastic Four #587 was a wonderful reading experience. Very emotionally moving as well as cinematic. It will be interesting to see how the series progresses from here. Knowing writer Jonathan Hickman’s deft characterization, I suspect that Ben will be incredibly affected, not only by guilt, but by being the sole witness and having to be the messenger for the others. This will be a devastating loss for those left behind, especially for the young children with which Hickman has been quietly populating the series, especially Franklin and Valeria.

The death is historically notable for the Human Torch character as both Johnny Storm and the first Torch were among the first characters of their respective comics eras — the original Timely-era character debuted in Marvel Comics #1 (1939) while Johnny (along with his Fantastic Four teammates) was one of the first characters of the Marvel Age in Fantastic Four #1 (1961). As others have pointed out, Johnny’s recent “death” doesn’t adhere to one of the key Gruenwald “rules” regarding comic book death — we didn’t see a dead body. So I expect we’ll see him again when we least expect it.

Or at least before we see the other two things discussed here today return.

KC CARLSON has already made plans to die without leaving a dead body. Just to make sure there’s always an “out” and to keep everyone on their toes.

WESTFIELD COMICS is not responsible for the stupid things that KC says. Especially that thing that really irritated you.

Comic covers from the Grand Comics Database.

USER COMMENTS

We'd love to hear from you, feel free to add to the discussion!